For mariners on long voyages, securing enough fresh water has long been a fundamental concern. Today, desalination technology has turned that challenge into a convenience, allowing boaters to convert seawater into clean, drinkable water wherever they travel. The technology has reshaped how long-distance cruisers plan their voyages and changed the way weekend boaters enjoy their time on the water.

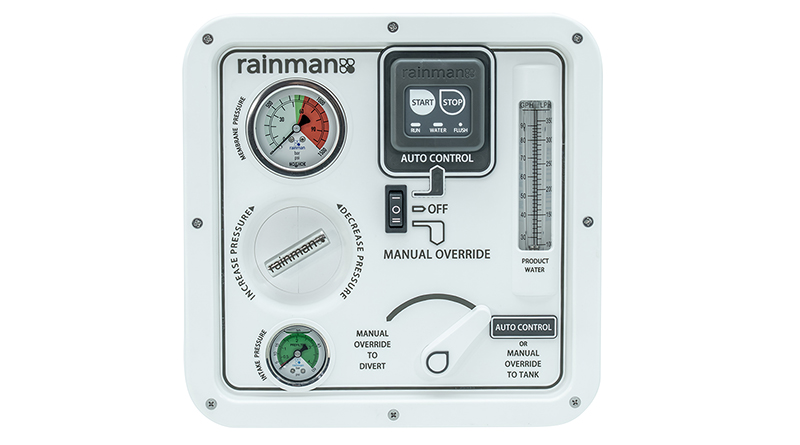

Image courtesy of Rainman

Desalination for recreational boating typically happens through a watermaker, a system that uses reverse osmosis to pump seawater at high pressure through a semi-permeable membrane. The process removes salt and minerals, producing water often cleaner than bottled water. That water can be used for drinking, cooking, showering, or rinsing salt from decks and fishing gear. For coastal cruisers, bluewater sailors, and liveaboards, a watermaker means fewer marina stops, less shower rationing, and greater independence while at anchor.

All modern watermakers work on the same principle. “Draw seawater in, filter it to 5 microns, put it under pressure, then pass it across a reverse osmosis membrane to extract fresh water from the filtered seawater,” explained Ron Schroeder, Managing Director of Rainman Watermakers, a brand that serves as one example of the systems available on the market.

Output varies depending on the system. Schroeder said Rainman’s units “can generate between 34 liters per hour (lph) (which is 9 gph (gallons per hour)) and 240 lph (63 gph). Our most popular system, by far, is the 140 lph (37 gph) system. It provides the best balance between system cost, power consumption, and freshwater output.”

Image courtesy of Rainman

Choosing a system often comes down to available power. Schroeder noted that AC-powered units are the most common among their customers. “With the ability to run from a 2kva generator or inverter, this is easily our most popular. As solar, battery, and inverter technology improve, people have more power available… Fill your tanks quickly and then get on with your day.” Petrol-driven models, he said, are useful for vessels without electricity or for those seeking maximum flexibility, though they have become a niche option as more boats have electrical systems onboard. DC-powered models work for smaller boats without generators or inverters, producing smaller amounts of water.

Watermakers also differ in how they are built and installed. Schroeder described portable units as “the simplest system to start with… used by simply throwing the intake hose overboard and placing it into your freshwater tank.” They require no invasive installation and can be moved between boats or stored at home, though they can be permanently installed later. Modular systems use the same internal components but are mounted separately to make use of available space. Framed units, which house most of the plumbing internally, are the easiest to install but require more space, making them more common on larger vessels.

Maintenance is straightforward but essential for long-term reliability. Schroeder said upkeep includes “changing prefilters when they get dirty, changing the lift pump impeller every year, and changing the oil in the high-pressure pump every year.” For longer-term storage, membranes can be flushed with fresh water or “pickled” for up to a year of idle time. With proper care, “the RO membranes should last five to seven years… but sometimes can go up to ten years.” He also noted that Rainman consumables are non-proprietary and widely available.

The rise of watermakers has changed the way sailors plan extended trips. In the past, crews calculated every stop around tank capacity. Now, some can remain off the grid for weeks or months. Options range from small, manual units for emergency drinking water to high-capacity systems producing hundreds of gallons per day. Affordability is also a factor; some boaters choose portable or entry-level models for occasional use, while others invest in permanently installed, high-output systems.

Advances in technology have expanded the market beyond ocean-crossing sailors. Energy recovery devices have reduced power consumption, and many systems are compatible with renewable energy sources like solar and wind. This has made them more appealing for coastal cruisers who value convenience and sustainability.

Environmental considerations are also part of the discussion. Recreational scale watermakers discharge a concentrated brine back into the sea, though the environmental impact is far smaller than that of industrial desalination plants. Energy use is another factor, with manufacturers responding by developing low-power and renewable-compatible designs.

For some crews, desalination has been a critical safety measure. Offshore racers or cruisers delayed by weather or mechanical issues have relied on watermakers to stay hydrated until reaching port. For others, the technology adds comfort — providing unlimited hot showers, spotless decks, and fresh cooking water for extended stays aboard.

Regardless of the reason for installing one, keeping a watermaker in peak condition is essential. Regular flushing, filter changes, and pump inspections can prevent costly repairs. Many owners align servicing with annual haul-outs to ensure their systems are ready before embarking on longer trips.

Whether using a portable model like the examples Schroeder describes, a permanently installed high-capacity system, or a small hand-pump unit kept for emergencies, modern desalination systems have given boaters the ability to travel farther, stay longer, and live more comfortably on the water.